When Will the Shroud of Turin Be on Display Again

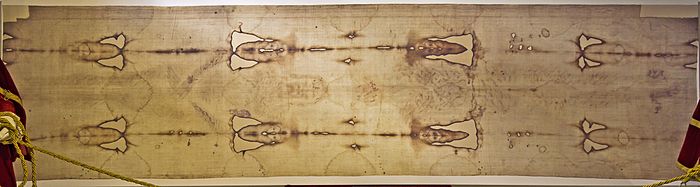

| Shroud of Turin | |

|---|---|

| The Shroud of Turin: modern photo of the face, positive (left), and digitally candy image (right) | |

| Textile | Linen |

| Size | 4.4 m × 1.ane m (fourteen ft 5 in × 3 ft 7 in) |

| Present location | Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist, Turin, Italy |

| Menses | 13th to 14th century[1] |

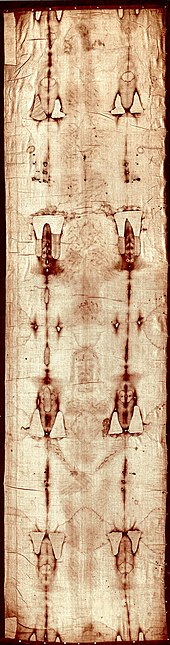

The Shroud of Turin (Italian: Sindone di Torino), also known as the Holy Shroud [2] [iii] (Italian: Sacra Sindone [ˈsaːkra ˈsindone] or Santa Sindone ), is a length of linen cloth bearing the negative prototype of a man. Some describe the image as depicting Jesus of Nazareth and believe the fabric is the burying shroud in which he was wrapped subsequently crucifixion.

First mentioned in 1354, the shroud was denounced in 1389 by the local bishop of Troyes as a fake. Currently the Catholic Church neither formally endorses nor rejects the shroud, and in 2013 Pope Francis referred to information technology as an "icon of a man scourged and crucified".[4] The shroud has been kept in the royal chapel of the Cathedral of Turin, in northern Italy, since 1578.[2]

In 1988, radiocarbon dating established that the shroud was from the Middle Ages, between the years 1260 and 1390.[5] All hypotheses put forward to challenge the radiocarbon dating have been scientifically refuted,[6] including the medieval repair hypothesis,[7] [eight] [9] the bio-contamination hypothesis[ten] and the carbon monoxide hypothesis.[11]

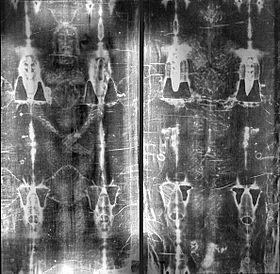

The image on the shroud is much clearer in black-and-white negative—first observed in 1898—than in its natural sepia color. A variety of methods have been proposed for the germination of the image, but the actual method used has not yet been conclusively identified.[12] The shroud continues to be intensely studied, and remains a controversial issue among scientists and biblical scholars.[13] [14] [15] [xvi]

Description [edit]

The shroud is rectangular, measuring approximately 4.4 by ane.1 metres (14 ft 5 in × 3 ft vii in). The cloth is woven in a three-to-one herringbone twill composed of flax fibrils. Its nigh distinctive characteristic is the faint, brownish paradigm of a front and back view of a naked man with his hands folded across his groin. The 2 views are aligned along the midplane of the body and point in opposite directions. The front and back views of the head nearly encounter at the eye of the cloth.[17]

The prototype in faint straw-yellow color on the crown of the cloth fibres appears to be of a man with a beard, moustache, and shoulder-length pilus parted in the center. He is muscular and alpine (various experts have measured him as from ane.seventy to i.88 k or five ft seven in to six ft 2 in).[18] Scarlet-brown stains are found on the cloth, correlating, co-ordinate to proponents, with the wounds in the Biblical description of the crucifixion of Jesus.[19]

In May 1898 Italian lensman Secondo Pia was allowed to photo the shroud. He took the first photograph of the shroud on 28 May 1898. In 1931, another lensman, Giuseppe Enrie, photographed the shroud and obtained results similar to Pia'south.[20] In 1978, ultraviolet photographs were taken of the shroud.[21] [22]

The shroud was damaged in a fire in 1532 in the chapel in Chambery, French republic. There are some burn holes and scorched areas down both sides of the linen, acquired by contact with molten silver during the burn that burned through it in places while it was folded.[23] Fourteen large triangular patches and viii smaller ones were sewn onto the cloth by Poor Clare nuns to repair the damage.

History [edit]

There are no definite historical records concerning the particular shroud currently at Turin Cathedral prior to the 14th century. A burial cloth, which some historians maintain was the Shroud, was endemic by the Byzantine emperors simply disappeared during the Sack of Constantinople in 1204.[24] Although in that location are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations before the 14th century, there is no historical evidence that these refer to the shroud currently at Turin Cathedral.[25]

The first possible historical record of the Shroud of Turin dates from 1353 or 1357,[xiii] [26] and the starting time sure tape is from 1390 when Bishop Pierre d'Arcis in Lirey, France wrote a memorandum to Antipope Clement VII (Avignon Obedience), stating that the shroud was a forgery and that the artist had confessed.[24] [27] Historical records seem to indicate that a shroud bearing an image of a crucified man existed in the small town of Lirey around the years 1353 to 1357 in the possession of a French Knight, Geoffroi de Charny, who died at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356.[13]

Some images of the Pray Codex are claimed by some to include a representation of the shroud. However the image on the Pray Codex has crosses on what may be one side of the supposed shroud, an interlocking step pyramid blueprint on the other, and no image of Jesus. Critics point out that it may not exist a shroud at all, but rather a rectangular tombstone, as seen on other sacred images.[28] A crumpled material can be seen discarded on the coffin, and the text of the codex fails to mention any miraculous image on the codex shroud.

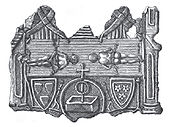

The pilgrim medallion of Lirey (earlier 1453),[29] drawing by Arthur Forgeais, 1865.

The history of the shroud from the 15th century is well recorded. In 1453 Margaret de Charny deeded the Shroud to the House of Savoy. In 1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in a chapel of Chambéry, capital of the Savoy region, where it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth. Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this impairment with patches. In 1578 Emmanuel Philibert, Knuckles of Savoy ordered the cloth to exist brought from Chambéry to Turin and it has remained at Turin ever since.[30]

Since the 17th century the shroud has been displayed in the chapel congenital for that purpose by Guarino Guarini.[31]) Repairs were made to the shroud in 1694 by Sebastian Valfrè to improve the repairs of the Poor Clare nuns.[32] Further repairs were made in 1868 by Princess Maria Clotilde of Savoy. The shroud remained the holding of the House of Savoy until 1983, when information technology was given to the Holy Run across by Umberto Two of Italy.[33]

The shroud was first photographed in the 19th century, during a public exhibition.

A fire, possibly caused past arson, threatened the shroud on eleven April 1997.[34] In 2002, the Holy Run into had the shroud restored. The cloth bankroll and thirty patches were removed, making it possible to photograph and scan the reverse side of the material, which had been hidden from view. A faint part-image of the body was found on the dorsum of the shroud in 2004.

The Shroud was placed back on public display (the 18th time in its history) in Turin from 10 April to 23 May 2010; and co-ordinate to Church building officials, more than 2 one thousand thousand visitors came to see it.[35]

On Holy Sabbatum (30 March) 2013, images of the shroud were streamed on various websites also as on boob tube for the offset time in 40 years.[36] [37] Roberto Gottardo of the diocese of Turin stated that for the first fourth dimension e'er they had released high definition images of the shroud that can be used on tablet computers and tin be magnified to testify details not visible to the naked eye.[36] As this rare exposition took place, Pope Francis issued a carefully worded statement which urged the true-blue to contemplate the shroud with awe just, like his predecessors, he "stopped firmly short of asserting its authenticity".[38] [39]

The shroud was again placed on brandish in the cathedral in Turin from 19 April 2015 until 24 June 2015. There was no charge to view information technology, but an appointment was required.[40]

Conservation [edit]

The shroud has undergone several restorations and several steps have been taken to preserve information technology to avoid further harm and contagion. Information technology is kept under laminated bulletproof glass in an airtight case. The temperature- and humidity-controlled case is filled with argon (99.5%) and oxygen (0.five%) to forbid chemical changes. The shroud itself is kept on an aluminum back up sliding on runners and stored flat within the example.[ citation needed ]

Religious views [edit]

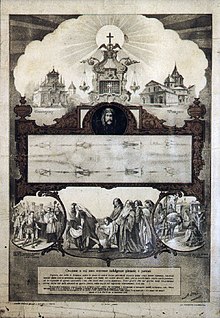

A poster advertizement the 1898 exhibition of the shroud in Turin. Secondo Pia's photograph was taken a few weeks too belatedly to be included in the poster. The image on the poster includes a painted face up, not obtained from Pia'due south photo.

The Gospels of Matthew,[41] Marker,[42] and Luke[43] state that Joseph of Arimathea wrapped the body of Jesus in a piece of linen cloth and placed it in a new tomb. The Gospel of John says he used strips of linen.[44]

Subsequently the resurrection, the Gospel of John[45] states: "Simon Peter came along behind him and went straight into the tomb. He saw the strips of linen lying at that place, also every bit the cloth that had been wrapped around Jesus' head. The cloth was still lying in its place, separate from the linen." The Gospel of Luke[46] states: "Peter, withal, got up and ran to the tomb. Bending over, he saw the strips of linen lying past themselves."

In 1543, John Calvin, in his volume Treatise on Relics, explained the reason why the Shroud cannot exist genuine:[47]

In all the places where they pretend to take the graveclothes, they prove a big slice of linen by which the whole body, including the head, was covered, and, accordingly, the figure exhibited is that of an entire body. But the Evangelist John relates that Christ was cached, "as is the way of the Jews to bury." What that fashion was may exist learned, not but from the Jews, by whom it is all the same observed, but also from their books, which explain what the ancient practice was. Information technology was this: The torso was wrapped up by itself equally far as the shoulders, so the head by itself was bound round with a napkin, tied past the four corners, into a knot. And this is expressed by the Evangelist, when he says that Peter saw the linen clothes in which the torso had been wrapped lying in ane place, and the napkin which had been wrapped about the head lying in another. The term napkin may mean either a handkerchief employed to wipe the face, or it may mean a shawl, but never means a large slice of linen in which the whole trunk may be wrapped. I have, however, used the term in the sense which they improperly give to it. On the whole, either the Evangelist John must have given a imitation business relationship, or every one of them must be convicted of falsehood, thus making it manifest that they have too impudently imposed on the unlearned.

Although pieces said to be of burial cloths of Jesus are held past at least four churches in French republic and iii in Italy, none has gathered as much religious following as the Shroud of Turin.[48] The religious beliefs and practices associated with the shroud predate historical and scientific discussions and have connected in the 21st century, although the Cosmic Church building has never passed judgment on its authenticity.[49] An example is the Holy Face Medal bearing the image from the shroud, worn by some Catholics.[50] Indeed, the Shroud of Turin is respected by Christians of several traditions, including Baptists, Catholics, Lutherans, Methodists, Orthodox, Pentecostals, and Presbyterians.[51] Several Lutheran parishes have hosted replicas of the Shroud of Turin, for didactic and devotional purposes.[52] [53]

Devotions [edit]

Although the shroud prototype is currently associated with Catholic devotions to the Holy Confront of Jesus, the devotions themselves predate Secondo Pia's 1898 photo. Such devotions had been started in 1844 by the Carmelite nun Marie of St Peter (based on "pre-crucifixion" images associated with the Veil of Veronica) and promoted by Leo Dupont, besides called the Apostle of the Holy Face. In 1851 Dupont formed the "Archconfraternity of the Holy Face up" in Tours, France, well earlier Secondo Pia took the photograph of the shroud.[54]

Miraculous image [edit]

The Vatican Veil of Veronica

The religious concept of the miraculous acheiropoieton (Greek: made without hands) has a long history in Christianity, going dorsum to at least the 6th century. Among the most prominent portable early acheiropoieta are the Epitome of Camuliana and the Mandylion or Epitome of Edessa, both painted icons of Christ held in the Byzantine Empire and now mostly regarded every bit lost or destroyed, as is the Hodegetria image of the Virgin Mary.[55] Other early images in Italy, all heavily and unfortunately restored, that take been revered as acheiropoieta now have relatively little following, as attending has focused on the Shroud.

Vatican position [edit]

In 1389, the bishop of Troyes sent a memorial to Antipope Cloudless VII, declaring that the cloth had been "artificially painted in an ingenious way" and that "it was likewise proved by the artist who had painted it that it was made by human work, not miraculously produced". In 1390, Clement Seven consequently issued four papal bulls, with which he allowed the exposition, merely ordered to "say aloud, to put an end to all fraud, that the aforementioned representation is not the true Shroud of Our Lord Jesus Christ, only a painting or console made to represent or imitate the Shroud ".[56] Withal, in 1506 Pope Julius II reversed this position and declared the Shroud to be authentic and authorized the public veneration of it with its ain mass and office.[57]

The Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano covered the story of Secondo Pia's photograph of 28 May 1898 in its edition of fifteen June 1898, but it did so with no annotate and thereafter Church officials generally refrained from officially commenting on the photograph for almost half a century.

The get-go official association between the image on the Shroud and the Catholic Church was made in 1940 based on the formal request by Sister Maria Pierina De Micheli to the curia in Milan to obtain authorisation to produce a medal with the prototype. The authorisation was granted and the offset medal with the image was offered to Pope Pius XII who approved the medal. The paradigm was and then used on what became known as the Holy Face Medal worn by many Catholics, initially as a means of protection during World State of war Ii. In 1958 Pope Pius XII approved of the image in association with the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus, and declared its feast to be celebrated every year the twenty-four hour period before Ash Wed.[58] [59] Following the approving by Pope Pius XII, Catholic devotions to the Holy Confront of Jesus have been well-nigh exclusively associated with the image on the shroud.

In 1936, Pope Pius XII chosen the Shroud a "holy matter perhaps similar nil else",[4] and went on to approve of the devotion accorded to it as the Holy Face up of Jesus.[60]

In 1998, Pope John Paul II called the Shroud a "distinguished relic" and "a mirror of the Gospel".[61] [62] His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, chosen it an "icon written with the blood of a whipped man, crowned with thorns, crucified and pierced on his right side".[4] In 2013, Pope Francis referred to it as an "icon of a man scourged and crucified".[four]

Other Christian denominations, such as Anglicans and Methodists, have also shown devotion to the Shroud of Turin.[51]

In 1983 the Shroud was given to the holy see past the House of Savoy.[63] Nonetheless, as with all relics of this kind, the Roman Catholic Church building fabricated no pronouncements on its authenticity. As with other approved Catholic devotions, the affair has been left to the personal conclusion of the faithful, as long as the Church does non effect a future notification to the reverse. In the Church building's view, whether the cloth is accurate or not has no bearing whatsoever on the validity of what Jesus taught or on the saving ability of his death and resurrection.[64]

Pope John Paul II stated in 1998 that:[65] "Since it is non a thing of faith, the Church has no specific competence to pronounce on these questions. She entrusts to scientists the job of standing to investigate, so that satisfactory answers may be found to the questions connected with this Sheet."[66] Pope John Paul Ii showed himself to exist deeply moved by the image of the Shroud and arranged for public showings in 1998 and 2000. In his address at the Turin Cathedral on Dominicus 24 May 1998 (the occasion of the 100th year of Secondo Pia's 28 May 1898 photo), he said: "The Shroud is an image of God's dear too as of human sin ... The banner left by the tortured trunk of the Crucified 1, which attests to the tremendous human being chapters for causing hurting and death to one'southward beau homo, stands as an icon of the suffering of the innocent in every historic period."[67]

On 30 March 2013, equally role of the Easter celebrations, there was an exposition of the shroud in the Cathedral of Turin. Pope Francis recorded a video message for the occasion, in which he described the image on the shroud as "this Icon of a human being", and stated that "the Man of the Shroud invites usa to contemplate Jesus of Nazareth."[38] [39] In his carefully worded argument Pope Francis urged the true-blue to contemplate the shroud with awe, just "stopped firmly short of asserting its actuality".[39]

Pope Francis went on a pilgrimage to Turin on 21 June 2015, to pray before, venerate the Holy Shroud and honor St. John Bosco on the bicentenary of his birth.[68] [69] [70]

Scientific analysis [edit]

Sindonology (from the Greek σινδών—sindon, the word used in the Gospel of Marking[15:46] to describe the type of the burying textile of Jesus) is the formal study of the Shroud. The Oxford English Dictionary cites the first use of this word in 1964: "The investigation ... assumed the stature of a separate field of study and was given a name, sindonology," but too identifies the use of "sindonological" in 1950 and "sindonologist" in 1953.[72]

Secondo Pia's 1898 photographs of the shroud allowed the scientific community to begin to report information technology. A variety of scientific theories regarding the shroud have since been proposed, based on disciplines ranging from chemistry to biological science and medical forensics to optical epitome analysis. The scientific approaches to the study of the Shroud fall into three groups: material analysis (both chemical and historical), biology and medical forensics and prototype analysis.

Early on studies [edit]

The first direct examination of the shroud past a scientific squad was undertaken in 1969–1973 in order to propose on preservation of the shroud and determine specific testing methods. This led to the appointment of an 11-member Turin Commission to advise on the preservation of the relic and on specific testing. 5 of the committee members were scientists, and preliminary studies of samples of the fabric were conducted in 1973.[13]

In 1976 physicist John P. Jackson, thermodynamicist Eric Jumper and photographer William Mottern used image analysis technologies developed in aerospace science for analyzing the images of the Shroud. In 1977 these three scientists and over 30 other experts in various fields formed the Shroud of Turin Research Projection. In 1978 this group, often called STURP, was given direct access to the Shroud.

Also in 1978, independently from the STURP research, Giovanni Tamburelli obtained at CSELT a 3D-elaboration from the Shroud with higher resolution than Jumper and Mottern. A 2nd result of Tamburelli was the electronic removal from the image of the blood that manifestly covers the face.[73]

Tests for pigments [edit]

In the 1970s a special eleven-fellow member Turin Commission conducted several tests. Conventional and electron microscopic exam of the Shroud at that time revealed an absenteeism of heterogeneous coloring fabric or pigment.[13] In 1979, Walter McCrone, upon analyzing the samples he was given by STURP, concluded that the prototype is actually made up of billions of submicrometre paint particles. The only fibrils that had been made bachelor for testing of the stains were those that remained affixed to custom-designed agglutinative tape applied to thirty-two different sections of the image.[74]

Marking Anderson, who was working for McCrone, analyzed the Shroud samples.[75] In his book Ray Rogers states that Anderson, who was McCrone's Raman microscopy expert, concluded that the samples acted as organic fabric when he subjected them to the laser.[76] : 61

John Heller and Alan Adler examined the same samples and agreed with McCrone's result that the fabric contains iron oxide. However, they concluded, the exceptional purity of the chemic and comparisons with other ancient textiles showed that, while retting flax absorbs iron selectively, the atomic number 26 itself was not the source of the image on the shroud.[19]

Radiocarbon dating [edit]

Subsequently years of discussion, the Holy Run into permitted radiocarbon dating on portions of a swatch taken from a corner of the shroud. Independent tests in 1988 at the Academy of Oxford, the Academy of Arizona, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Engineering concluded with 95% conviction that the shroud cloth dated to 1260–1390 AD.[5] This 13th- to 14th-century dating is much too contempo for the shroud to take been associated with Jesus. The dating does on the other hand match the showtime appearance of the shroud in church history.[77] [78] This dating is also slightly more recent than that estimated past art historian West. S. A. Dale, who postulated on creative grounds that the shroud is an 11th-century icon made for utilise in worship services.[79]

Some proponents for the authenticity of the shroud accept attempted to disbelieve the radiocarbon dating event by claiming that the sample may represent a medieval "invisible" repair fragment rather than the prototype-begetting fabric.[24] [80] [10] [seven] [81] [82] [83] [84] Withal, all of the hypotheses used to challenge the radiocarbon dating accept been scientifically refuted,[11] [half-dozen] including the medieval repair hypothesis,[7] [8] the bio-contagion hypothesis[10] and the carbon monoxide hypothesis.[eleven]

In contempo years several statistical analyses take been conducted on the radiocarbon dating data, attempting to draw some conclusions almost the reliability of the C14 dating from studying the data rather than studying the shroud itself. They have all concluded that the data shows a lack of homogeneity, which might exist due to unidentified abnormalities in the fabric tested, or else might be due to differences in the pre-testing cleaning processes used by the unlike laboratories. The most recent analysis (2020) concludes that the stated engagement range needs to be adjusted by up to 88 years in social club to properly run into the requirement of "95% confidence".[85] [86] [87] [88]

Material historical analysis [edit]

Historical fabrics [edit]

In 1998, shroud researcher Joe Nickell wrote that no examples of herringbone weave are known from the fourth dimension of Jesus. The few samples of burial cloths that are known from the era are made using plain weave.[27] In 2000, fragments of a burial shroud from the 1st century were discovered in a tomb most Jerusalem, believed to accept belonged to a Jewish high priest or member of the aristocracy. The shroud was composed of a uncomplicated two-way weave, different the complex herringbone twill of the Turin Shroud. Based on this discovery, the researchers concluded that the Turin Shroud did non originate from Jesus-era Jerusalem.[89] [90] [91]

Biological and medical forensics [edit]

Blood stains [edit]

There are several reddish stains on the shroud suggesting blood, simply it is uncertain whether these stains were produced at the aforementioned time every bit the image, or after.[92] McCrone (see painting hypothesis) believed these as containing iron oxide, theorizing that its presence was likely due to unproblematic pigment materials used in medieval times.[93]

Skeptics cite forensic claret tests whose results dispute the authenticity of the Shroud, and betoken to the possibility that the blood could belong to a person who handled the shroud, and that the credible blood flows on the shroud are unrealistically nifty.[94] [95] [96]

Flowers and pollen [edit]

A study published in 2011 past professor Salvatore Lorusso of the University of Bologna and others subjected 2 photographs of the shroud to detailed modern digital image processing, one of them being a reproduction of the photographic negative taken by Giuseppe Enrie in 1931. They did not discover whatever images of flowers or coins or anything else on either image.[97]

In 2015, Italian researchers Barcaccia et al. published a new written report in Scientific Reports. They examined the human being and not-man Dna found when the shroud and its backing cloth were vacuumed in 1977 and 1988. They plant traces of 19 dissimilar plant taxa, including plants native to Mediterranean countries, Central Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Eastern asia (People's republic of china) and the Americas. Of the homo mtDNA, sequences were found belonging to haplogroups that are typical of various ethnicities and geographic regions, including Europe, North and East Africa, the Center Eastward and India. A few non-plant and non-human sequences were besides detected, including various birds and 1 ascribable to a marine worm common in the Northern Pacific Sea, next to Canada.[98] After sequencing some Deoxyribonucleic acid of pollen and dust found on the shroud, they confirmed that many people from many different places came in contact with the shroud. According to the scientists, "such diversity does not exclude a Medieval origin in Europe but information technology would exist as well compatible with the historic path followed by the Turin Shroud during its presumed journey from the Near East. Furthermore, the results raise the possibility of an Indian manufacture of the linen textile."[98]

Anatomical forensics [edit]

Total length negatives of the shroud.

A number of studies on the anatomical consistency of the paradigm on the shroud and the nature of the wounds on it have been performed, following the initial written report by Yves Delage in 1902.[71] While Delage declared the epitome anatomically flawless, others take presented arguments to support both authenticity and forgery.

The analysis of a crucified Roman, discovered near Venice in 2007, shows heel wounds that are consistent with those found on Jehohanan but which are not consequent with wounds depicted on the shroud. Also, neither of the crucifixion victims known to archaeology show prove of wrist wounds.[99]

Joe Nickell in 1983, and Gregory S. Paul in 2010, separately country that the proportions of the image are not realistic. Paul stated that the face and proportions of the shroud paradigm are impossible, that the figure cannot represent that of an bodily person and that the posture was inconsistent. They argued that the forehead on the shroud is likewise minor; and that the artillery are too long and of different lengths and that the distance from the eyebrows to the tiptop of the head is non-representative. They concluded that the features can be explained if the shroud is a piece of work of a Gothic artist.[27] [100]

In 2018 an experimental Bloodstain Blueprint Analysis (BPA) was performed to report the behaviour of blood flows from the wounds of a crucified person, and to compare this to the bear witness on the Turin Shroud. The comparison between different tests demonstrated that the claret patterns on the forearms and on the back of the hand are not connected, and would take had to occur at unlike times, as a result of a very specific sequence of movements. In add-on, the rivulets on the front of the image are not consistent with the lines on the lumbar area, even supposing there might have been dissimilar episodes of bleeding at different times. These inconsistencies suggest that the Turin linen was an artistic or "didactic" representation, rather than an authentic burying shroud.[101]

Image and text analysis [edit]

Paradigm analysis [edit]

Both fine art-historical, digital paradigm processing and analog techniques have been applied to the shroud images.

In 1976 scientists analysed a photograph of the shroud paradigm using NASA imaging equipment, and found that the shroud paradigm has the property of decoding into a 3-dimensional prototype.[102] Optical physicist and one-time STURP member John Dee German has noted that it is non difficult to make a photograph which has 3D qualities. If the object being photographed is lighted from the forepart, and a non-reflective "fog" of some sort exists between the photographic camera and the object, then less light volition reach and reverberate back from the portions of the object that are farther from the lens, thus creating a contrast which is dependent on altitude.[103]

The image on the front of the Turin Shroud, 1.95 metres (6 ft five in) long, is not exactly the same size as the paradigm on the dorsum, 2.02 metres (half dozen ft viii in) long.[104] Analysis of the images found them to be uniform with the shroud having been used to wrap a torso 1.75 metres (5 ft 9 in) long.[104]

If Jesus' dead body actually produced the images on the shroud, 1 would expect the bodily areas touching the ground to be more distinct. In fact, Jesus' hands and face are depicted with great detail, while his buttocks and his navel are faintly outlined or invisible, a discrepancy explained with the artist's consideration of modesty. Too, Jesus' right arm and hand are abnormally elongated, assuasive him to modestly comprehend his genital surface area, which is physically impossible for an ordinary dead body lying supine. No wrinkles or other irregularities distort the image, which is improbable if the cloth had covered the irregular grade of a body. For comparison, run into oshiguma; the making of face-prints as an artform, in Nihon. Furthermore, Jesus' concrete advent corresponds to Byzantine iconography.[105] [106] [107]

Hypotheses on image origin [edit]

Painting [edit]

The technique used for producing the prototype is, according to Walter McCrone, described in a book about medieval painting published in 1847 by Charles Lock Eastlake (Methods and Materials of Painting of the Nifty Schools and Masters). Eastlake describes in the affiliate "Do of Painting By and large During the XIVth Century" a special technique of painting on linen using tempera paint, which produces images with unusual transparent features—which McCrone compares to the prototype on the shroud.[108]

Acrid pigmentation [edit]

In 2009, Luigi Garlaschelli, professor of organic chemistry at the University of Pavia, stated that he had made a total size reproduction of the Shroud of Turin using but medieval technologies. Garlaschelli placed a linen sheet over a volunteer and and then rubbed it with an acidic pigment. The shroud was then aged in an oven before being washed to remove the paint. He then added blood stains, scorches and water stains to replicate the original.[109] Giulio Fanti, professor of mechanical and thermic measurements at the Academy of Padua, commented that "the technique itself seems unable to produce an prototype having the about disquisitional Turin Shroud image characteristics".[110] [111]

Garlaschelli'south reproduction was shown in a 2010 National Geographic documentary. Garlaschelli'southward technique included the bas-relief arroyo (described beneath) just only for the paradigm of the face. The resultant image was visibly similar to the Turin Shroud, though lacking the uniformity and detail of the original.[112]

Medieval photography [edit]

The art historian Nicholas Allen has proposed that the image on the shroud was formed by a photographic technique in the 13th century.[113] Allen maintains that techniques already available before the 14th century—e.g., as described in the Volume of Optics, which was at only that time translated from Arabic to Latin—were sufficient to produce primitive photographs, and that people familiar with these techniques would take been able to produce an image as institute on the shroud. To demonstrate this, he successfully produced photographic images like to the shroud using only techniques and materials available at the time the shroud was supposedly made.[114] [115] [116]

All the same, according to Mike Ware, a chemist and good on the history of photography, Allen's proposal "encounters serious obstacles with regard to the technical history of the lens. Such claimants tend to draw upon the wisdom of hindsight to project a distorted historical perspective, wherein their cases rest upon a detail chain of procedures which is exceedingly improbable; and their 'proofs' corporeality only to demonstrating (none too faithfully) that it was non totally impossible." Amid other difficulties, Allen's hypothesized process would have required that the subject field (Jesus's corpse) be exposed, motionlessly, in the sun for months.[117]

Grit-transfer technique [edit]

Scientists Emily Craig and Randall Bresee have attempted to recreate the likenesses of the shroud through the dust-transfer technique, which could take been done by medieval arts. They beginning did a carbon-dust drawing of a Jesus-like confront (using collagen grit) on a newsprint fabricated from forest pulp (which is similar to 13th- and 14th-century paper). They next placed the drawing on a table and covered it with a piece of linen. They then pressed the linen confronting the newsprint by firmly rubbing with the flat side of a wooden spoon. By doing this they managed to create a ruby-red-brownish image with a lifelike positive likeness of a person, a iii-dimensional prototype and no sign of brush strokes.[118]

Bas-relief [edit]

In 1978, Joe Nickell noted that the Shroud image had a iii-dimensional quality and thought its creation may accept involved a sculpture of some type. He advanced the hypothesis that a medieval rubbing technique was used to explain the image, and set out to demonstrate this. He noted that while wrapping a cloth around a sculpture with normal contours would result in a distorted image, Nickell believed that wrapping a cloth over a bas-relief might result in an image similar the one seen on the shroud, as information technology would eliminate wraparound distortions. For his demonstration, Nickell wrapped a wet textile around a bas-relief sculpture and allowed it to dry out. He so applied powdered pigment rather than wet paint (to prevent information technology soaking into the threads). The paint was applied with a dauber, similar to making a rubbing from a gravestone. The consequence was an paradigm with dark regions and light regions assuredly arranged. In a photo essay in Pop Photography magazine, Nickell demonstrated this technique stride-by-step.[27] [119] [note 1] Other researchers afterwards replicated this procedure.

In 2005, researcher Jacques di Costanzo synthetic a bas-relief of a Jesus-similar face and draped wet linen over it. After the linen dried, he dabbed information technology with a mixture of ferric oxide and gelatine. The result was an image similar to that of the face on the Shroud. The imprinted prototype turned out to be wash-resistant, impervious to temperatures of 250 °C (482 °F) and was undamaged by exposure to a range of harsh chemicals, including bisulphite which, without the gelatine, would ordinarily have degraded ferric oxide to the compound ferrous oxide.[120]

Instead of painting, it has been suggested that the bas-relief could also be heated and used to scorch an paradigm onto the cloth. However researcher Thibault Heimburger performed some experiments with the scorching of linen, and found that a scorch marker is simply produced by directly contact with the hot object—thus producing an all-or-nada discoloration with no graduation of color equally is found in the shroud.[121]

Maillard reaction [edit]

The Maillard reaction is a form of not-enzymatic browning involving an amino acid and a reducing saccharide. The cellulose fibers of the shroud are coated with a sparse saccharide layer of starch fractions, various sugars, and other impurities. The potential source for amines required for the reaction is a decomposing body,[76] : 100 and no signs of decomposition accept been establish on the Shroud. Rogers likewise notes that their tests revealed that there were no proteins or bodily fluids on the image areas.[76] : 38 Too, the prototype resolution and the compatible coloration of the linen resolution seem to be incompatible with a machinery involving diffusion.[122]

Fringe theories [edit]

Images of coins, flowers and writing [edit]

Various people have claimed to have detected images of flowers on the shroud, likewise equally coins over the optics of the face in the image, writing and other objects.[123] [124] [125] [126] [127] [128] [129] [130] [131] Withal a written report published in 2011 by Lorusso and others subjected ii photographs of the shroud to detailed modernistic digital image processing, one of them being a reproduction of the photographic negative taken past Giuseppe Enrie in 1931. They did not find any images of flowers or coins or writing or any other boosted objects on the shroud in either photograph, they noted that the faint images were "only visible by incrementing the photographic dissimilarity", and they concluded that these signs may be linked to protuberances in the yarn, and possibly also to the amending and influence of the texture of the Enrie photographic negative during its development in 1931.[97] The use of coins to cover the eyes of the expressionless is non attested for 1st-century Palestine. The existence of the money images is rejected by most scientists.[132]

Radiation processes [edit]

Some proponents for the authenticity of the Shroud of Turin take argued that the image on the shroud was created by some course of radiation emission at the "moment of resurrection".[133] [134] [135] Still, STURP member Alan Adler has stated that this theory is not by and large accepted as scientific, given that it runs counter to the laws of physics.[133] Raymond Rogers also criticized the theory, saying: "It is clear that a corona discharge (plasma) in air will cause hands observable changes in a linen sample. No such effects can be observed in image fibers from the Shroud of Turin. Corona discharges and/or plasmas made no contribution to image formation."[76] : 83

See also [edit]

- Depiction of Jesus

- Relics associated with Jesus

- Seamless robe

Notes [edit]

- ^ For his pigment, Nickell first used the burial spices myrrh and aloes, but changed to red iron oxide (the pigment red ocher) when microanalyst, Walter McCrone identified it as constituting the shroud's image. (McCrone had identified the blood every bit red ochre and vermilion tempers paint.)[27]

References [edit]

- ^ Taylor, R.E. and Bar-Yosef, Ofer. Radiocarbon Dating, Second Edition: An Archaeological Perspective. Left Coast Press, 2014, p. 165.

- ^ a b "Shroud of Turin | History, Description, & Authenticity". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Turin Shroud: full text of Pope Francis' comments". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Pope Francis and the Shroud of Turin". National Catholic Reporter. i April 2013. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b Damon, P. East.; Donahue, D. J.; Gore, B. H.; Hatheway, A. 50.; Jull, A. J. T.; Linick, T. West.; Sercel, P. J.; Toolin, L. J.; Bronk, C. R.; Hall, Due east. T.; Hedges, R. E. M.; Housley, R.; Law, I. A.; Perry, C.; Bonani, M.; Trumbore, S.; Woelfli, W.; Ambers, J. C.; Bowman, S. 1000. E.; Leese, 1000. N.; Tite, One thousand. South. (16 Feb 1989). "Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin" (PDF). Nature. 337 (6208): 611–615. Bibcode:1989Natur.337..611D. doi:10.1038/337611a0. S2CID 27686437.

- ^ a b Radiocarbon Dating, Second Edition: An Archaeological Perspective, By R.E. Taylor, Ofer Bar-Yosef, Routledge 2016; pp. 167–168.

- ^ a b c R. A. Freer-Waters, A. J. T. Jull, "Investigating a Dated piece of the Shroud of Turin", Radiocarbon 52, 2010, pp. 1521–1527.

- ^ a b Schafersman, Steven D. (14 March 2005). "A Skeptical Response to Studies on the Radiocarbon Sample from the Shroud of Turin by Raymond Due north. Rogers". llanoestacado.org . Retrieved ii January 2016. Archived 16 March 2019 at the Wayback Car

- ^ The Shroud, past Ian Wilson; Random Firm, 2010, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c Gove, H. E. (1990). "Dating the Turin Shroud: An Cess". Radiocarbon. 32 (ane): 87–92. doi:10.1017/S0033822200039990.

- ^ a b c Professor Christopher Ramsey, Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, Oxford University, March 2008, at https://c14.arch.ox.air-conditioning.uk/shroud.html

- ^ Ball, P. (2008). "Material witness: Shrouded in mystery". Nature Materials. seven (v): 349. Bibcode:2008NatMa...7..349B. doi:10.1038/nmat2170. PMID 18432204.

- ^ a b c d e Meacham, William (1983). "The Authentication of the Turin Shroud, An Issue in Archeological Epistemology". Current Anthropology. 24 (3): 283–311. doi:10.1086/202996. JSTOR 2742663. S2CID 143781662.

- ^ According to LLoyd A. Currie, it is "widely accustomed" that "the Shroud of Turin is the single most studied antiquity in homo history". Currie, Lloyd A. (2004). "The Remarkable Metrological History of Radiocarbon Dating". Journal of Research of the National Found of Standards and Technology. 109 (two): 200. doi:10.6028/jres.109.013. PMC4853109. PMID 27366605.

- ^ Habermas, G. R. (2011). "Shroud of Turin". In Kurian, G. T. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 2161.

- ^ "Is Information technology a Imitation? DNA Testing Deepens Mystery of Shroud of Turin". Alive Science . Retrieved ix April 2018.

- ^ Adler, Alan D. (2002). The orphaned manuscript: a gathering of publications on the Shroud of Turin. p. 103. ISBN978-88-7402-003-iv.

- ^ "How Tall is the Man on the Shroud?". ShroudOfTurnForJournalists.com . Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ a b Heller, John H. (1983). Report on the Shroud of Turin. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN978-0-395-33967-1.

- ^ Scott, John Beldon (2003). Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin. University of Chicago Press. p. 302. ISBN978-0-226-74316-v.

- ^ Miller, V. D.; Pellicori, Southward. F. (July 1981). "Ultraviolet fluorescence photography of the Shroud of Turin". Journal of Biological Photography. 49 (3): 71–85. PMID 7024245.

- ^ Pellicori, Southward. F. (1980). "Spectral properties of the Shroud of Turin". Applied Eyes. 19 (12): 1913–1920. Bibcode:1980ApOpt..19.1913P. doi:10.1364/AO.19.001913. PMID 20221155.

- ^ Cruz, Joan Carroll (1984). Relics. Our Sunday Visitor. p. 49. ISBN978-0-87973-701-6.

- ^ a b c Poulle, Emmanuel (December 2009). "Les sources de l'histoire du linceul de Turin. Revue critique". Revue d'Histoire Ecclésiastique. 104 (3–4): 747–782. doi:x.1484/J.RHE.iii.215.

- ^ Humber, Thomas: The Sacred Shroud. New York: Pocket Books, 1980. ISBN 0-671-41889-0

- ^ "Turin shroud 'older than thought'". BBC News. 31 January 2005.

- ^ a b c d e Joe Nickell, Inquest on the Shroud of Turin: Latest Scientific Findings, Prometheus Books, 1998, ISBN 9781573922722

- ^ G.Chiliad.Rinaldi, "Il Codice Pray", http://sindone.weebly.com/pray.html

- ^ Catalogue of the Musée National du Moyen Age, Paris, A gift from Lirey past Mario Latendresse

- ^ See Firm of Savoy historian Filiberto Pingone in Filiberto Pingone, La Sindone dei Vangeli (Sindon Evangelica). Componimenti poetici sulla Sindone. Bolla di papa Giulio 2 (1506). Pellegrinaggio di S. Carlo Borromeo a Torino (1578). Introduzione, traduzione, note e riproduzione del testo originale a cura di Riccardo Quaglia, nuova edizione riveduta (2015), Biella 2015, ISBN 978-1-4452-8258-ix

- ^ John Beldon Scott, Architecture for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin, Academy of Chicago Press, 2003, ISBN 0-226-74316-0, p. xxi

- ^ Compages for the shroud: relic and ritual in Turin past John Beldon Scott 2003 ISBN 0-226-74316-0, p. 26.

- ^ "Shroud of Turin Given to Vatican by Former King of Italia". The Washington Postal service . Retrieved ten March 2022.

- ^ "Shroud of Turin Saved From Fire in Cathedral". The New York Times. 12 April 1997.

- ^ "To see the Shroud : 2M and counting" Archived 27 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Zenit. 5 May 2010

- ^ a b Povoledo, Elisabetta (29 March 2013). "Turin Shroud Going on Television receiver, With Video From Pope". New York Times . Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ "Turin Shroud shown live on Italy Idiot box". BBC News. 30 March 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ a b Pope: "I join all of y'all gathered before the Holy Shroud". The Vatican Today. Retrieved 3 Apr 2013

- ^ a b c "Pope Francis and the Turin Shroud: Making sense of a mystery" (31 March 2013). The Economist. Retrieved 3 April 2013

- ^ "Turin Shroud goes back on display at metropolis'due south cathedral". BBC News. nineteen April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Matthew 27:59–60

- ^ Marking 15:46

- ^ Luke 23:53

- ^ John nineteen:38–xl

- ^ John 20:6–7

- ^ Luke 24:12

- ^ An Admonition showing, the Advantages which Christendom might derive from an Inventory of Relics

- ^ Joan Carrol Cruz, 1984 Relics ISBN 0-87973-701-viii, p. 55

- ^ Ann Brawl, Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices, Our Sunday Visitor, 2002 ISBN 0-87973-910-X, p. 533

- ^ Ann Ball, Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices, Our Dominicus Visitor, 2002, ISBN 0-87973-910-X, p. 239

- ^ a b Dreisbach, Albert R. (2001). "A theological basis for sindonology & its ecumenical implications". Collegamento pro Sindone.

Some 20 years agone this ecumenical dimension of this sacred linen became very evident to me on the night of Baronial xvi, 1983, when local judicatory leaders offered their corporate blessing to the Turin Shroud Showroom and participated in the Evening Office of the Holy Shroud. The Greek Archbishop, the Roman Cosmic Archbishop, the Episcopal Bishop and the Presiding Bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church building gathered before the world's outset full size, backlit transparency of the Shroud and joined clergy representing the Assemblies of God, Baptists, Lutherans, Methodists and Presbyterians in an amazing witness to ecumenical unity.

- ^ Trautmann, Erik (7 October 2015). "Shroud of Turin replica on showroom at St. Peter's Lutheran Church". The Hr . Retrieved nine May 2018.

- ^ Dickerson, Hillary (8 April 2014). "Replica Shroud of Turin on display at St. Matthew". Galena Gazette. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ^ Dorothy Scallan, The Holy Man of Tours, TAN Books and Publishers, 2009, ISBN 0-89555-390-2

- ^ Kitzinger, Ernst (1954). "The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. viii: 83–150. doi:10.2307/1291064. JSTOR 1291064.

- ^ "Gli scienziati credono nel dubbio- Torino LASTAMPA.information technology". 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Shroud of Turin (relic)". Encyclopædia Britannica, 28 December 2010

- ^ Maria Rigamonti, Mother Maria Pierina, Cenacle Publishing, 1999

- ^ Joan Carroll Cruz, "Saintly Men of Mod Times", Our Sunday Company, 2003, ISBN ane-931709-77-7

- ^ Joan Carroll Cruz, Saintly Men of Modern Times, Our Lord's day Visitor, 2003, ISBN 1-931709-77-seven, p. 200.

- ^ "Pope Francis and the Shroud of Turin - National Cosmic Reporter". April 2013. Retrieved six June 2016.

- ^ Pastoral Visit of His Holiness John Paul 2 to Vercelli and Turin, Italy, 23–24 May 1998 [one]

- ^ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing, ISBN 0-87973-454-Ten, p. 57

- ^ Matthew Bunson, OSV's encyclopedia of Catholic history, revised edition, Our Sunday Visitor, 2004, ISBN 1-59276-026-0, p. 912

- ^ Francis D'Emilio article on Pope John Paul 2'southward visit to the Shroud of Turin, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 25 May 1998

- ^ "Address of John Paul II". The Holy Encounter - Vatican web site. 24 May 1998. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Pope John Paul II (24 May 1998). Accost in Turin Cathedral (Speech). Turin, Italia. Archived from the original on 11 May 2000.

- ^ "Pope Francis to pray before the Holy Shroud in Turin". Romereports.com . Retrieved vi June 2016.

- ^ "Pope Francis to Venerate Famed Shroud of Turin in 2015". six November 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ "Pope will visit Shroud of Turin, commemorate birth of St. John Bosco". Ncronlone.org – National Catholic Resporter. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ a b Delage, Yves (1902). "Le Linceul de Turin". Revue Scientifique. 22: 683–687.

- ^ "Sindonology, n.". Oxford English Lexicon . Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Tamburelli, Giovanni (Nov 1981). "Some Results in the Processing of the Holy Shroud of Turin". IEEE Transactions on Design Analysis and Auto Intelligence. PAMI-3 (6): 670–676. doi:ten.1109/TPAMI.1981.4767168. PMID 21868987. S2CID 17987034.

- ^ McCrone, W. C., Skirius, C., The Microscope, 28, 1980, pp i–13; McCrone, W. C., The Microscope, 29, 1981, pp. nineteen–38. The Microscope 1980, 28, 105, 115; 1981, 29, 19; Wiener Berichte uber Naturwissenschaft in der Kunst 1987/1988, four/v, fifty and Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 77–83.

- ^ Materials evaluation, Volume forty, Issues 1–5, 1982, Folio 630

- ^ a b c d Rogers, Raymond N. (2008). A Chemist's Perspective On The Shroud of Turin. Lulu Printing, Inc. ISBN978-0615239286.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "news.nationalgeographic.com Why Shroud of Turin'south Secrets Continue to Elude Scientific discipline". National Geographic, 17 April 2015

- ^ Dale, West.Due south.A. (1987). "The Shroud of Turin: Relic or Icon?". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Enquiry. B29 (one–2): 187–192. Bibcode:1987NIMPB..29..187D. doi:10.1016/0168-583X(87)90233-3. This paper is significant in that it was presented to the international radiocarbon community shortly before radiocarbon dating was performed on the shroud.

- ^ Rogers, Raymond Northward. (20 January 2005). "Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin" (PDF). Thermochimica Acta. 425 (i–2): 189–194. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2004.09.029. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ S. Benford; J. Marino (July–August 2008). "Discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area of the Turin shroud" (PDF). Chemistry Today. 26 (4): four–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Riani, Marco; Atkinson, Anthony C.; Fanti, Giulio; Crosilla, Fabio (27 April 2012). "Regression assay with partially labelled regressors: carbon dating of the Shroud of Turin". Statistics and Computing. 23 (4): 551–561. doi:10.1007/s11222-012-9329-5. S2CID 6060870.

- ^ Busson, P. "Sampling error?" Letter in Nature, Vol. 352, 18 July 1991, p. 187.

- ^ Robert Villarreal, "Belittling Results On Thread Samples Taken From The Raes Sampling Expanse (Corner) of the Shroud Cloth" Abstract Archived 11 Oct 2008 at the Wayback Machine (2008)

- ^ Riani, Marco; Atkinson, Anthony C.; Fanti, Giulio; Crosilla, Fabio (27 April 2012). "Regression assay with partially labelled regressors: carbon dating of the Shroud of Turin". Statistics and Computing. Springer Scientific discipline and Business Media LLC. 23 (four): 551–561. doi:10.1007/s11222-012-9329-five. ISSN 0960-3174. S2CID 6060870.

- ^ Casabianca, T.; Marinelli, E.; Pernagallo, G.; Torrisi, B. (22 March 2019). "Radiocarbon Dating of the Turin Shroud: New Testify from Raw Data". Archaeometry. Wiley. 61 (5): 1223–1231. doi:10.1111/arcm.12467. ISSN 0003-813X. S2CID 134747250.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan; Schwalbe, Larry (2020). "An instructive inter-laboratory comparison: The 1988 radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin". Journal of Archaeological Scientific discipline: Reports. Elsevier BV. 29: 102015. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102015. ISSN 2352-409X.

- ^ JMP; Ball, Philip (9 Apr 2019). "How old is the Turin Shroud?". Chemistry World . Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "DNA of Jesus-era shrouded homo in Jerusalem reveals primeval case of leprosy". Physorg.com. xvi Dec 2009. Retrieved 16 Dec 2009.

- ^ Bong, Bethany (sixteen Dec 2009). "'Jesus-era' burial shroud plant". BBC News . Retrieved xvi December 2009.

- ^ "Shroud of Turin Not Jesus', Tomb Discovery Suggests". National Geographic Daily News. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- ^ Heller, John H.; Adler, Alan D. (15 August 1980). "Claret on the Shroud of Turin". Applied Optics. nineteen (16): 2742–2744. Bibcode:1980ApOpt..19.2742H. doi:x.1364/AO.19.002742. PMID 20234501.

- ^ McCrone Research, Initial Exam – 1979, retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "shroud of Turin". Skepdic.com. 23 August 2000. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ^ Baden, Michael. 1980. Quoted in Reginald West. Rhein, Jr., "The Shroud of Turin: Medical examiners disagree". Medical Globe News, 22 Dec, p. fifty.

- ^ McCrone in Wiener Berichte uber Naturwissenschaft in der Kunst 4/5, fifty 1987/1988.

- ^ a b Salvatore Lorusso, Chiara Matteucci, Andrea Natali, Tania Chinni, Laura Solla (2011). "The Shroud of Turin betwixt history and science: an ongoing debate". Conservation Scientific discipline in Cultural Heritage. Vol 11, University of Bologna.

- ^ a b Barcaccia, Gianni; Galla, Giulio; Achilli, Alessandro; Olivieri, Anna; Torroni, Antonio (v Oct 2015). "Uncovering the sources of Deoxyribonucleic acid establish on the Turin Shroud". Scientific Reports. 5: 14484. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514484B. doi:10.1038/srep14484. PMC4593049. PMID 26434580.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (2018). "Crucifixion Evidence Debunks Turin 'Shroud'". Skeptical Inquirer. 42 (5): 7.

- ^ Paul, Gregory Southward. (6 May 2010). "The Shroud of Turin: The Not bad Gothic Fine art Fraud". Secular Web Kiosk. Internet Infidels. Retrieved ix May 2010.

- ^ A BPA Approach to the Shroud of Turin; past Matteo Borrini Ph.D. and Luigi Garlaschelli Thou.Sc. Journal of Forensic Sciences; Volume 64, Issue 1; January 2019; pp. 137–143; https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13867; view at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1556-4029.13867

- ^ Heller, John H. Report on the Shroud of Turin, Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0-395-33967-seven, p. 207.

- ^ J. Dee German. "On the Visibility of the Shroud Prototype" (PDF) . Retrieved half-dozen June 2016.

- ^ a b Fanti, Grand.; Basso, R.; Bianchini, Grand. (2010). "Turin Shroud: Compatibility Between a Digitized Torso Image and a Computerized Anthropomorphous Manikin". Periodical of Imaging Science and Technology. 54 (5): 050503. doi:10.2352/J.ImagingSci.Technol.2010.54.five.050503.

- ^ "SHROUD OF TURIN", New Cosmic Encyclopedia (2d ed.), 2003

- ^ Raymond E. Brown. Biblical Exegesis and Church Doctrine (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1985), pp. 150–152

- ^ Raymond E. Brownish (15 August 2002). Biblical Exegesis and Church Doctrine. Wipf & Stock Publishers. pp. 150–152. ISBN978-ane-59244-024-5.

- ^ Walter C. McCrone, Judgment day for the Shroud of Turin, Amherst, NY. Prometheus Books, (1999) ISBN ane-57392-679-5

- ^ Garlaschelli, L. (2010). "Life-size Reproduction of the Shroud of Turin and its Image". Periodical of Imaging Science and Technology. 54 (4): 040301. doi:10.2352/J.ImagingSci.Technol.2010.54.4.040301.

- ^ Heimburger T., Fanti Yard., "Scientific Comparing betwixt the Turin Shroud and the First Handmade Whole Copy", International Workshop on the Scientific Arroyo to the Acheiropoietos Images, 2010

- ^ Fanti, G.; Heimburger, T. (2011). "Letter of the alphabet to the Editor Comments on 'Life-Size Reproduction of the Shroud of Turin and Its Image' by L. Garlaschelli". Periodical of Imaging Scientific discipline and Technology. 55 (ii): 020102. doi:10.2352/j.imagingsci.technol.2011.55.ii.020102.

- ^ "Remaking the Shroud". Channel.nationalgeographic.com. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Nicholas P Fifty Allen, Verification of the Nature and Causes of the Photo-negative Images on the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. L. (1993) "Is the Shroud of Turin the get-go recorded photo?" The S African Periodical of Art History, eleven November, 23–32

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. L. (1994)A reappraisal of belatedly thirteenth-century responses to the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin: encolpia of the Eucharist, vera eikon or supreme relic? The Southern African Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 4 (1), 62–94

- ^ Allen, Nicholas P. Fifty. (1998)The Turin Shroud and the Crystal Lens. Empowerment Technologies Pty. Ltd., Port Elizabeth, Southward Africa

- ^ Ware, Mike (1997). "On proto-photography and the Shroud of Turin". History of Photography. 21 (4): 261–269. doi:ten.1080/03087298.1997.10443848.

- ^ Craig, Emily A, Bresee, Randal R, "Image Formation and the Shroud of Turin", Journal of Imaging Science and Technology, Volume 34, Number 1, 1994

- ^ Nickell, Joe. "The Turin Shroud: False? Fact? Photograph?". Popular Photography. November 1979: 97–147.

- ^ Ingham, Richard (21 June 2005). "Turin Shroud Confirmed as Fake". Physorg.com. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Thibault Heimburger. "The Turin Shroud Body Image: The Scorch Hypothesis Revisited" (PDF) . Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Fanti, G.; Botella, J. A.; Di Lazzaro, P.; Heimburger, T.; Schneider, R.; Svensson, N. (2010). "Microscopic and Macroscopic Characteristics of the Shroud of Turin Image Superficiality". Periodical of Imaging Science and Engineering. 54 (iv): 040201. doi:10.2352/J.ImagingSci.Technol.2010.54.4.040201.

- ^ Danin, Avinoam (1998). "Where Did the Shroud of Turin Originate? A Botanical Quest". ERETZ Magazine. No. November/December.

- ^ Sheler, Jeffery L. (24 July 2000). "Shroud of Turin - Mysteries of History". U.South. News & Globe Written report. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved xix Dec 2010.

- ^ Jackson, John P., Eric J. Jumper, Bill Mottern, and Kenneth E. Stevenson. 1977. "The three-dimensional epitome of Jesus' burying material", Proceedings, 1977 United States Briefing of Enquiry on The Shroud of Turin, Holy Shroud Club, New York, 1977, pp. 74–94.

- ^ F. Filas, The dating of the Shroud from coins of Pontius Pilate, Cogan, Youngtown (Arizona), 1982

- ^ N. Balossino, L'immagine della Sindone, ricerca fotografica e informatica, Editrice Elle Di Ci, 1997, ISBN 88-01-00798-1

- ^ A. Marion, A.-Fifty. Courage, Nouvelles découvertes sur le suaire de Turin, Paris, Albin Michel, 1998, ISBN two-226-09231-5

- ^ Guscin, Marker. "The 'Inscriptions' on the Shroud" (PDF). British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter Nov 1999.

- ^ Owen, Richard (21 November 2009). "Decease certificate is imprinted on the Shroud of Turin, says Vatican scholar". The Times . Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Daily Telegraph: "Jesus Christ'south 'death certificate' found on Turin Shroud" [ii]

- ^ Lombatti, Antonio (1997). "Doubts Concerning the Coins Over the Eyes". British Society for the Turin Shroud Newsletter (45).

- ^ a b The Shroud of Turin by Bernard Ruffin 1999 ISBN 0-87973-617-8, pp. 155–156

- ^ Jackson, John P.; Jumper, Eric J.; Ercoline, William R. (15 July 1984). "Correlation of epitome intensity on the Turin Shroud with the three-D structure of a human body shape". Practical Optics. 23 (xiv): 2244. Bibcode:1984ApOpt..23.2244J. doi:x.1364/AO.23.002244. PMID 18212985.

- ^ M. Carter, "Formation of the Image on the Shroud of Turin", American Chemical Gild Volume on Archaeological Chemistry, 1983

Further reading [edit]

- Picknett, Lynn and Prince, Clive: The Turin Shroud: In Whose Image?, Harper-Collins, 1994 ISBN 0-552-14782-6.

- Antonacci, Mark : The Resurrection of the Shroud, M. Evans & Co., New York 2000, ISBN 0-87131-890-three

- Whiting, Brendan, The Shroud Story, Harbour Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-646-45725-X

- Di Lazzaro, Paolo (ed.) : Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Scientific Arroyo to the Acheiropoietos Images, ENEA, 2010, ISBN 978-88-8286-232-ix.

- Olmi, Massimo, Indagine sulla croce di Cristo, Torino 2015 ISBN 978-88-6737-040-5

- Jackson, John, The Shroud of Turin. A Critical Summary of Observations, Information, and Hypotheses, CMJ Marian Publishers, 2017, ISBN 9780692885734

External links [edit]

- Sindone.org – official site of the custodians of the shroud in Turin

- Professor Creates 3D Paradigm From Shroud

- The Shroud of Turin Website – Shroud of Turin Education and Research Clan, Inc. website

- Turin Shroud Middle of Colorado – research heart of Dr. John Jackson, a leading member of the STURP squad

- Expert Science, Bad Science, and the Shroud of Turin – 2014 NYUAD Chemical science lecture on YouTube

- Unwrapping the Shroud – 2009 Discovery channel documentary on YouTube

- Shroud of Turin Prove – 2008 BBC documentary on YouTube

- Barrie Schwortz interview – EWTN interview with photographer Barrie Shwortz on YouTube

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shroud_of_Turin

0 Response to "When Will the Shroud of Turin Be on Display Again"

Enregistrer un commentaire